On Creative Connections Innovative Change and Change in the Arts

Looking at the evolution of international cultural

cooperation and the parameters affecting it, Corina

Şuteu analyses current challenges and the ongoing

change of cultural paradigms. She argues that cultural

actors should take an active role, abandoning utilitarian

conceptions of culture and raising it up instead to

its true value in society. She also suggests the need

for a deeper understanding of the positive impact that

past generations of cultural actors have had and the need

to empower individuals to build strategies for change.

Un lapsus al lui Cristian Mungiu

Într-un interviu recent la B1, discutînd despre deosebita vizibilitate pe care noul val din cinematografia românească a adus-o României în ultimii ani, regizorul Cristian Mungiu deplîngea faptul că nici o instituţie a statului nu a înţeles că trebuie să susţină în mod constant, coerent şi semnificativ reuşitele cineaştilor şi să consolideze această fereastră de oportunitate pe care filmele autohtone, atît de premiate şi de mediatizate internaţional în ultimii ani, au deschis-o imaginii României în lume.

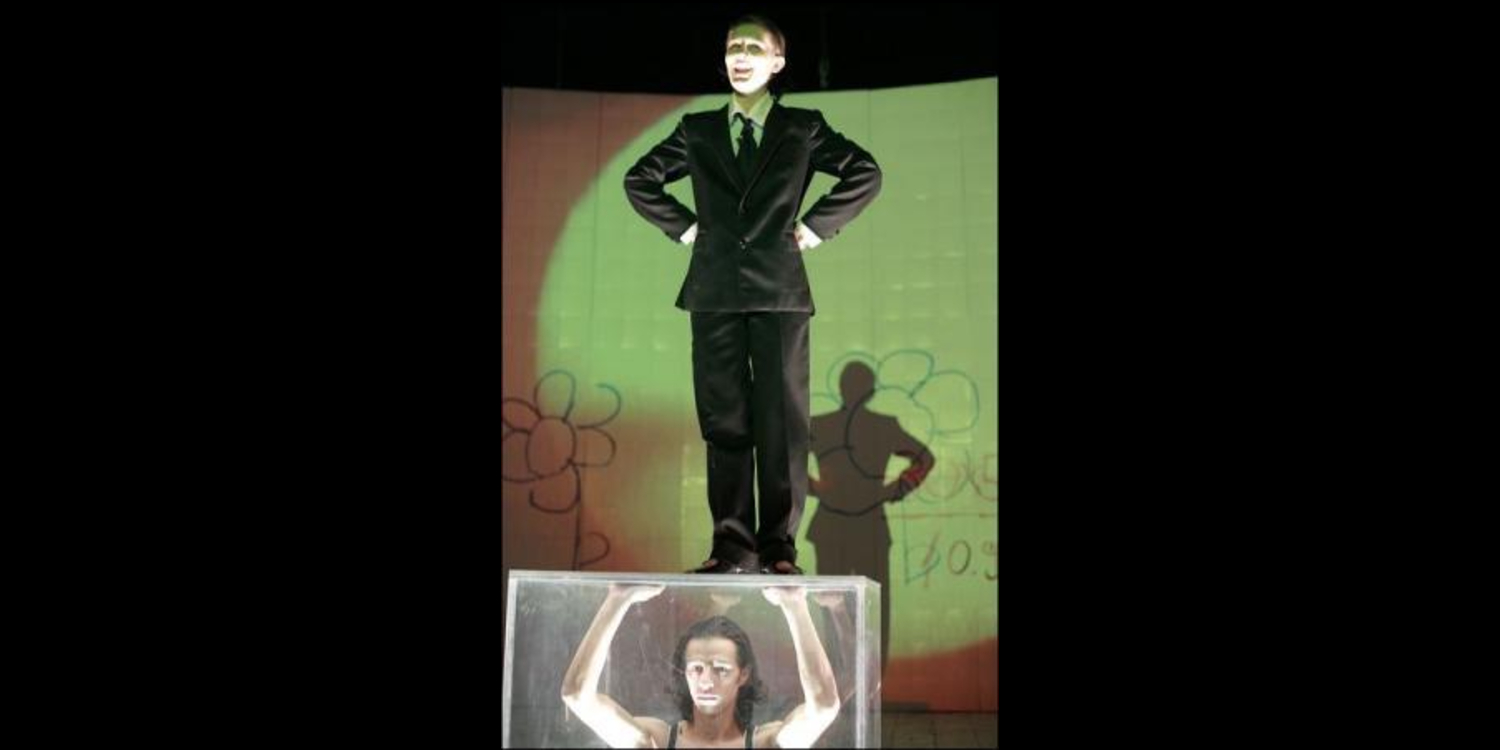

ANDREI ŞERBAN AND THE TRAVELING ACADEMY: ABOUT CREATIVITY AND THE INNER SELF

In 1990, immediately after the fall of communism, Andrei Şerban

arrived in Romania from the United States. He was invited at the time to

become managing director of the National Theatre in Bucharest. Şerban

eagerly accepted the offer and soon took over the difficult challenge, perfectly

aware that there was much to be done and that the results had to be both

immediately visible and quantifiable in the long term. He was ready to try to

reshape the post-communist Romanian theatre and give it a new form and

creative energy, capable of nourishing fresh beginnings. He stubbornly strove

to turn this energy into the seeding ground for a decontaminated emotional

life to be offered to the people of Romania, who had been so alienated and

enfeebled by their totalitarian past.

Arts Don’t Have to Know How to Behave – A Commentary on Street art in Contemporary Urban Surroundings

From the outset, the issue of street art, as presented in the

following pages, will be considered more in its creative dimension

than in its political one. The interest of the ideas explored lies in

knowing how much today this kind of art is part of a more general

resurgence of a wider creative process. Also, the perspective

chosen as well as the style (an ad hoc commentary using direct

observation of street art practices and set in a general historical

context based on cultural studies in Europe) are aimed at pinpointing

some critical landmarks and at paving the way for further

comments and ideas.

State on Stage – The impact of public policies on the performing arts in Europe

Government support for the Performing Arts in EU member states.

Experiences, perspectives, best practices.

International Conference on behalf of Pearle.

New York–ul din mine.

New York este un oras in care intri asa cum ai intra intr- o carte buna. Primul lucru pe care il simti este un fel de tremur interior, foarte intim , greu de transmis in cuvinte. O bucurie a intilnirii cu ceva neasteptat, care te scoala din orice letargie, te surprinde si te inhata fara sa ai timp sa te aperi.

Orasul pare ca un val urias, iti pica in fata si te da peste cap, dupa care, cind iti recistigi echilibrul, te poarta in suvoiul unei energii teribile, orice impotrivire fiind imposibila.

The art of making choices and the choice to work with the arts

Policy choices when heading an already existing art organization are difficult to make and even more difficult to keep. And they have to be made quickly and clearly because in arts and culture, like in business, the quicker one gets the lot!

The Year of Intercultural dialogue – a challenge for Romanian democratic practices

In February 2008, just at the moment when programs of the year of Intercultural dialogue were

launched in Romania, one of the national representatives in the EU parliament, Ioan Mircea

Pascu, was expressing his indignation about the programming of ‘California Dreaming’ as part

of the Parliament’s film festival dedicated to this very issue.

The Necessary Awakening

Since the fall of communism sixteen years ago, few issues regarding the development and orientation of European cultural policy have achieved consensus among informed analysts. However, most accept the idea that 1990 marked not only the end of post-WWII division between Eastern and Western Europe, but also a radical, tangible shift in the ways European public administrations approach involvement with cultural affairs.

Not afraid to be an Alien

For having being involved in networking activities for 15 years now, I heard much about the post networking ‘era’ and about the imminent collapse of European networks. Well, that was a wrong hypothesis and it seems even more so if we consider that European cultural networking succeeded in changing, in a radical way since the 80’s, the stiff diplomatic vocabulary and the sometimes too conservatory cooperation practices of cultural and artistic interaction. TransEuropeHalles is, in this respect, a brilliant example of networking reshaping and reinvestment (I do not believe there are even other cultural networks in Europe that had 60 meetings since their foundation).

Keynote > Are there collectively held values in learning which are recognized in , and shared by, several cultures while remaining respectful of cultural distinctiveness ?

In a book published in 20002

, the French sociologist and philosopher Edgar Morin is underlining

the need to produce a context for new humanistic studies, based on two complementary and

antagonistic pillars: the integrated study of sciences and of humanities.

Note on the type of products and distribution networks that could be used on behalf of the Council of Europe’s initiative “Cultural identities and shared values of citizenship”

The following note intends to draw a synthetic picture of a number of elements and proposals that could render more effective the Council of Europe’s initiative in the field of ‘cultural identity and shared values of citizenship’.

An informed observer would start by addressing, however, a couple of critical aspects that render this task less easy and appealing than it might seem.

Special issue on Cultural Policies in CEE > Policy Warning and Forecast Report

“ We are at the beginning of a new era, characterized by great insecurity,

permanent crisis and the absence of any kind of status quo (…) There are no

victors and no defeated powers today, not even in Eastern Europe”- “In from the

margins”, Council of Europe report, 1997, quote at the beginning of chapter “The

geopolitics of culture”

Cultural policies in transition, the issue of participation and the challenge of democracy

The direct and indirect effects that cultural policies had on the development of Western

European societies after the Second World War is one of the issues that the cultural

community has to deal with today.2

In order to understand how the cultural sector in the

post communist countries of South East Europe tackle this issue, as they struggle to

reinvent and to reposition their cultural policies on their government agendas; in order to

understand which traditional, but also which new instruments they employ and why; the

degree of inspiration they receive from western models; and last but not least, how

cultural policy is contributing to the design of new democracies, this article will attempt to

offer some keys, based on the broad and surprising experience of the Policies for

Culture programme (2000-2004), as well as on the broader background.3

Challenges of Cultural Cooperation in Southeastern Europe: the Internationalization of Cultural Policies and Practices

The cultural cooperation logic marking the last 14 years in Southeastern Europe (SEE) has to be

regarded from a broad perspective as driven not only by the consequences of the collapse of the

communist institutional order, but also as a result of the general transformations taking place at a

European and international level: the challenges resulting from the liberalization of markets,

globalization processes and technological revolution (new technologies, information support for

knowledge, deepening inequality North/South, the redefinition of the role of culture and the

growing tendency towards transversal governance, replacing the pyramidal paradigm of

authority).

Born in Illyria or “How to build cultural cooperation with (South ) Eastern Europe”

It was two days after the first of May glittering EU enlargement ceremonies

ended. As usual before one of my trips to somewhere in Europe, I was taking the

taxi in Nantes and saying bye-bye in Romanian to my sixteen year old daughter,

who, despite her French schooling, still speaks her mother tongue pretty well.

As I prepared to leave, the young French taxi driver looked on with what I

thought to be the average curiosity that we are now so used to, after ten years of

‘where does your accent come from?’ and, ‘what is your nationality, Madame, if

I am not too indiscreet…?’

Cultural Policy Curriculum Development & Mobility Support for Lecturers in Central and Eastern Europe

MOTTO: ‘Cultural policy does not yet exist as a clearly defined area of study with

agreed research paradigms and methodologies. It rather comprises a loose

articulation of work emerging from different disciplinary origins – from arts

management, communication studies, urban studies, cultural studies, cultural

economics – and is not yet able to readily identify how its different parts add up

to a cohesive whole’ (Tony Bennett, Colin Mercer: ‘Recasting Cultural Policies –

Improving Research and International Cooperation in Cultural Policies’, 1996)

Despre necesitatea unui statut special al artistului. Exemplul ţărilor postcomuniste

Dacă în mod obişnuit încercăm să găsim motivele caracterului de “în afara normelor” al profesiunii de artist din perspectiva trăsăturilor distinctive între profesiuni zise “normale” şi profesiunea artistică3, cu toate acestea, o altă analiză, mai convingătoare şi mai subtilă, poate fi avansată. Ea pleacă de la următoarea întrebare: care este munca furnizată de artist şi pentru care este remunerat? Cum definim profesiunea unui artist?

The empowerment of civil society agents in new democracies

The notion of civil society and the emergence of an effectively democratic civil sector in post communist countries is in the centre of the present argument.

New cultural policies should be , in former communist countries, designed according first and foremost to the axiomatic lack of democratic behaviour that these societies are showing still now and focus very strongly on the civic empowerment of the individuals that are independent opinion leaders.

The cultural policy and the artist or how to build in SEEurope “a sample continent for the innovation principle”

In his book published in 2002, “Portrait of an artist as worker”, French sociologist Pierre

Michel Menger is developing an interesting theory that places the artist and the specificity of

his type of labour as a symbol of the new kind of relationship established by the modern

world between the individual at work and his environment. He is stating that the image of the

artistic creativity is today more and more perceived as a crucial factor in the universe of

productivity, and the very special status and characteristics of the artistic work: dealing with

complexity, being innovative and autonomous, flexible and mobile corresponds more and

more to the requested profile of the new man at labour in the western society. Arts are for

Menger “laboratories of flexibility” and the artist’s type of labour profile embodies the profile

of the modern worker.

Academic training in cultural management in Europe: making it work

The following paper will only address a limited part of the complexity of issues

related to the academic training in cultural management regarded from a comparative,

European perspective. Its aim its to highlight a number of key topics of concern and offer a

broad perspective to further specialized debate. The perspective chosen is related in many

aspects to the author’s background. As director of a MA course in European cultural

management for the last eight years, but also as cultural operator in Europe, she is very much

aware about the importance of the present momentum to revise and reshape the reflection

dedicated to a discipline that only academically gained generalized legitimacy ten to fifteen

years ago in the whole of European countries.

Cultural Institutions after 12 years of “New Democracy” in Central and Eastern Europe

Social exclusion disempowers people. It deprives them of access to

experience of the arts – when faced, as a substantial number of

people in Eastern Europe have been, with stark choices of

survival, going to the theater or cinema can hardly be expected to

be on their list of priorities. International declarations on access to

participation in cultural life are academic to those living in

poverty.1

Cultural Institutions in Transition

Cultural institutions worldwide face new challenges to their financial sustainability, their organizational structures and their social relevance. This is particularly true in the European countries and the former Soviet Union. While the political and social changes in these regions differ greatly, the effects of economic liberalization in its many forms have fundamentally altered the context in which cultural organizations operate. With this context in mind, the Salzburg Seminar proposed that the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Seminar might jointly explore ideas for a program that could meet the needs of European cultural institutions.