Category Archives: Article

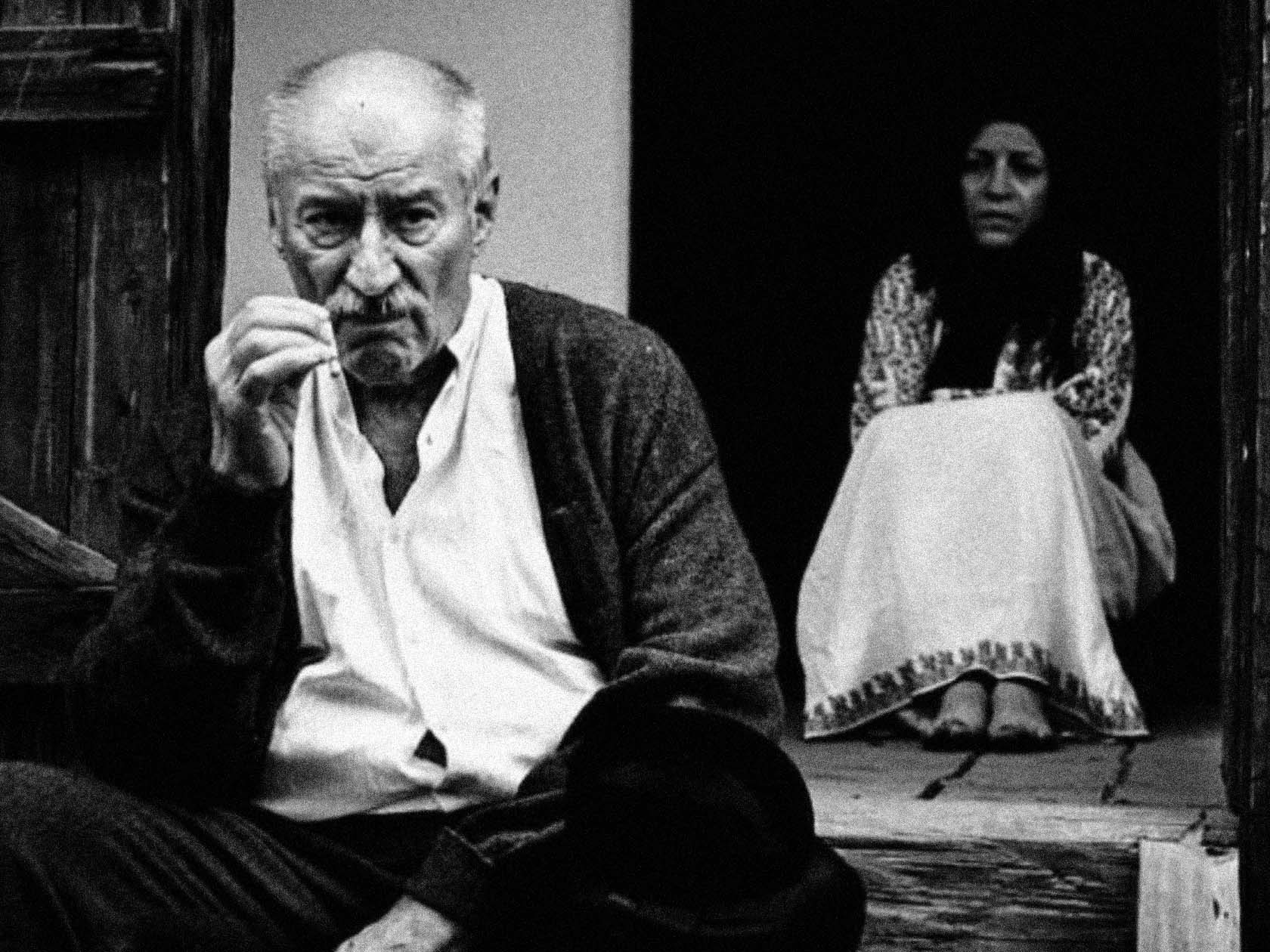

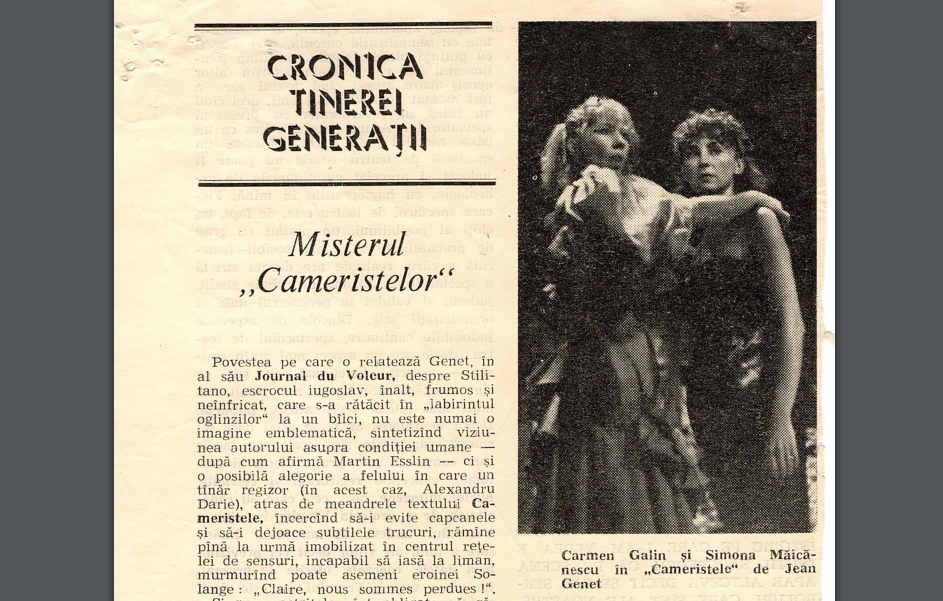

Cronica Tinerei Generații – Misterul ‘Cameristelor’

Revista Teatrul – noiembrie 1988

From Collectivism to Connectivism – The Romanian Arts Sector since the Fall of Communism

For former communist countries like Romania a ‘crisis’ of the cultural

system can be claimed. It is demonstrated by a lack of long-term cultural

policies and of answers to questions about the benefit of public support for

the arts in order to transfer the country to a new system after the upheaval

of 1989. This crisis stems from the diminished role of cultural and education

policies as compared to other fields of public policy as well as from

an outdated administration apparatus dealing with the cultural dynamics.

Therefore, cultural management and its tools are often used here in a purely

functional way, with no philosophy of mission behind.

On Creative Connections Innovative Change and Change in the Arts

Looking at the evolution of international cultural

cooperation and the parameters affecting it, Corina

Şuteu analyses current challenges and the ongoing

change of cultural paradigms. She argues that cultural

actors should take an active role, abandoning utilitarian

conceptions of culture and raising it up instead to

its true value in society. She also suggests the need

for a deeper understanding of the positive impact that

past generations of cultural actors have had and the need

to empower individuals to build strategies for change.

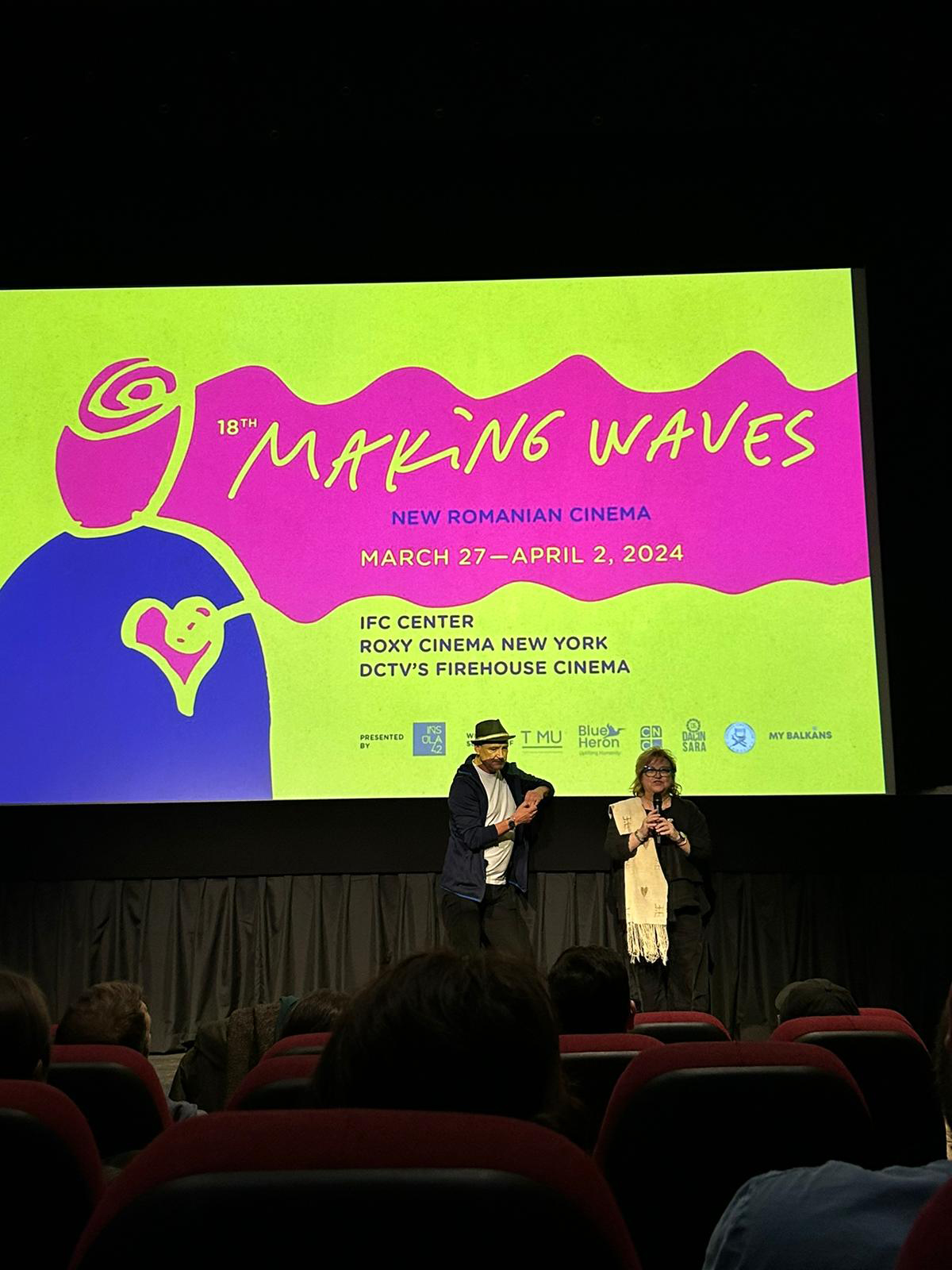

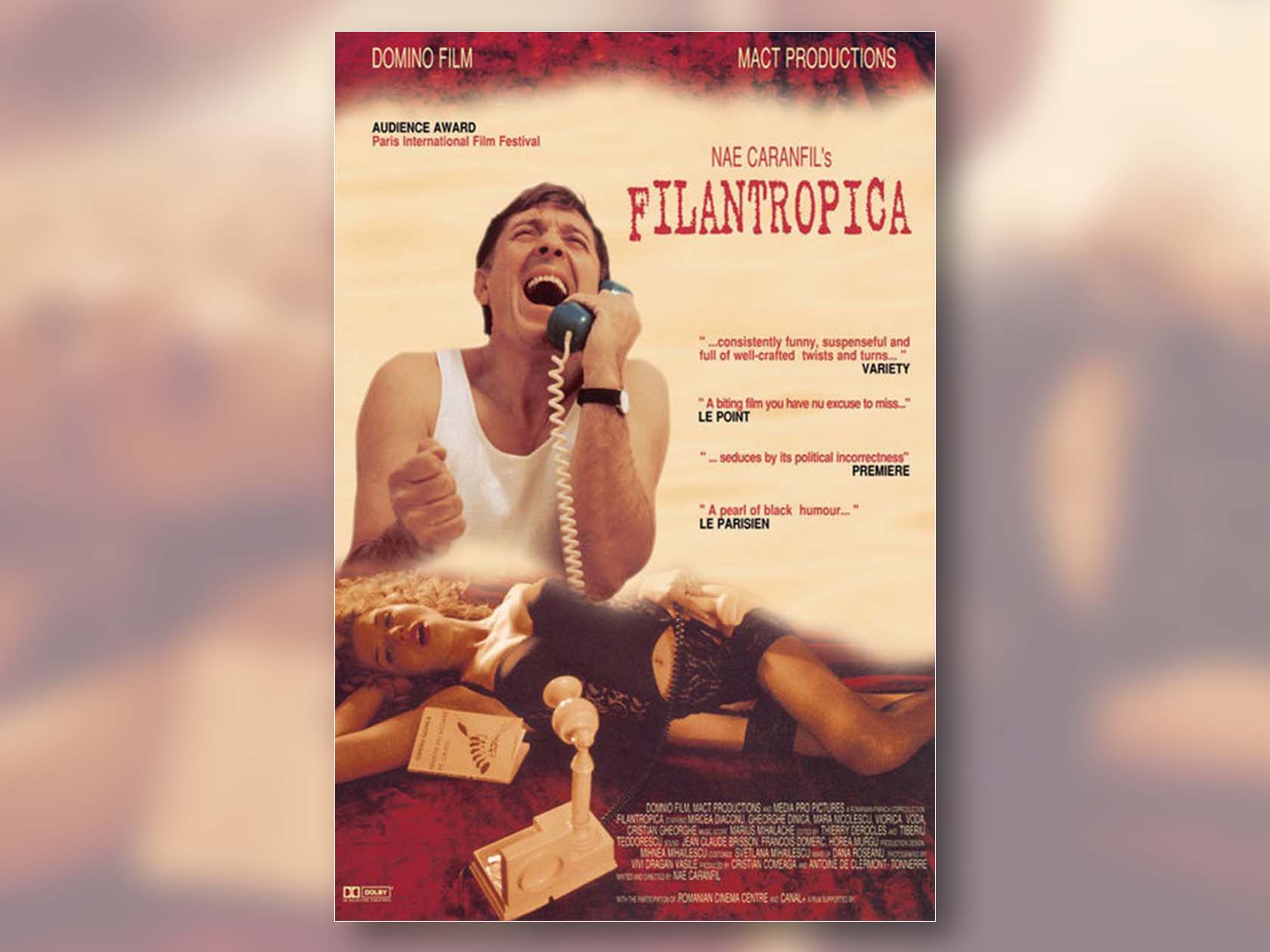

Un lapsus al lui Cristian Mungiu

Într-un interviu recent la B1, discutînd despre deosebita vizibilitate pe care noul val din cinematografia românească a adus-o României în ultimii ani, regizorul Cristian Mungiu deplîngea faptul că nici o instituţie a statului nu a înţeles că trebuie să susţină în mod constant, coerent şi semnificativ reuşitele cineaştilor şi să consolideze această fereastră de oportunitate pe care filmele autohtone, atît de premiate şi de mediatizate internaţional în ultimii ani, au deschis-o imaginii României în lume.

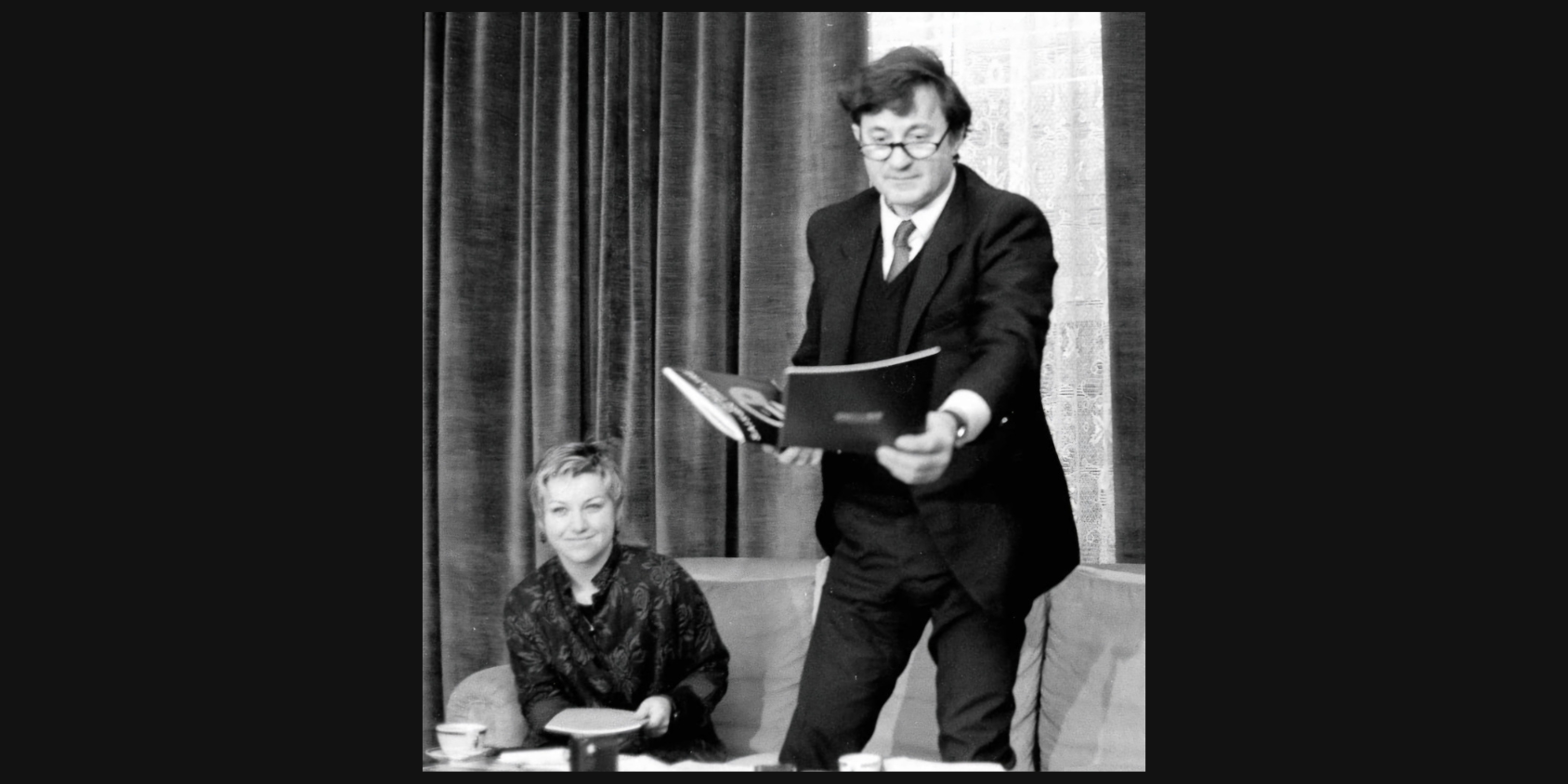

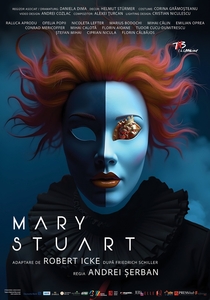

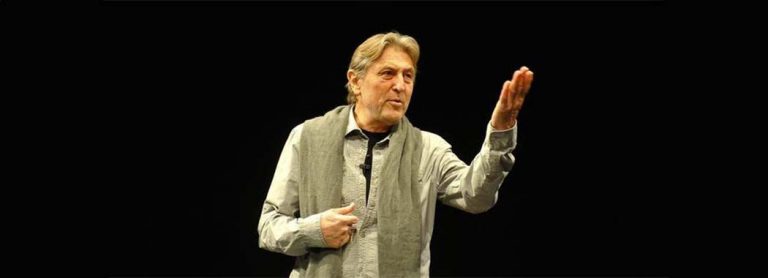

ANDREI ŞERBAN AND THE TRAVELING ACADEMY: ABOUT CREATIVITY AND THE INNER SELF

In 1990, immediately after the fall of communism, Andrei Şerban

arrived in Romania from the United States. He was invited at the time to

become managing director of the National Theatre in Bucharest. Şerban

eagerly accepted the offer and soon took over the difficult challenge, perfectly

aware that there was much to be done and that the results had to be both

immediately visible and quantifiable in the long term. He was ready to try to

reshape the post-communist Romanian theatre and give it a new form and

creative energy, capable of nourishing fresh beginnings. He stubbornly strove

to turn this energy into the seeding ground for a decontaminated emotional

life to be offered to the people of Romania, who had been so alienated and

enfeebled by their totalitarian past.